History and Complaints Toxic Annular Tears of the Lumbar Spine

I’m Dr. Tony Mork, author, speaker, endoscopic spine specialist. Today I’d like to talk about Toxic Annular Tears of Lumbar Spine. I use the term “toxic” to indicate the annular tears that hurt. This is because not all annular tears hurt, in fact most don’t. The annular tears that do hurt are responsible for a lot of disability and a lot of confusion. Toxic annular tears are probably the most under-diagnosed and frustrating cause of chronic low back pain for several reasons…

There is a lot to cover on this topic of toxic annular tears, so I’m going to divide it into five parts.

- In Part 1, I will talk about the history and the typical complaints I hear. I will describe the person who has an annular tear, how they describe it, and the frustration they can experience and feel when they seek treatment.

- In Part 2 - We will talk about the different ways to diagnose an annular tear.

- In Part 3 - we will look at what an annular tear is and why they hurt.

- In Part 4 - we will talk about why toxic annular tears cause so much confusion, with their odd presentations of groin and testicle pain to foot pain without a disc herniation.

- In Part 5 - we will discuss various treatment options for annular tears. These options will make a lot more sense, once you understand the basic problem.

Ok, let’s get started with part 1, The history and typical complaints of toxic annular tears of the lumbar spine.

The patient history of an annular tear can be summarized in three words.

- Recurrent (“My back goes out for no reason.”)

- Frustrating (“Nobody knows what to do.”)

- Disabling (“You need several days of bed rest before the pain goes away.”)

If you have a long history of low back pain, it’s very likely that you have seen a medical professional who ordered an MRI to evaluate the problem. Often, the MRI “didn’t show too much.” Sometimes there will be a disc bulge or small protrusion, dark disc, high intensity zone or annular tear, but nothing definitive. Nothing to really account for your back “giving away” or intermittent agonizing back pain that can leave you bedridden for days.

Confusion arises because most annular tears seen on an MRI do not hurt. Since the majority of tears do not hurt, they are often overlooked as possible causes of pain, especially since there are no clear treatment options. The fact is that there is no way to tell from an MRI that an annular tear is toxic or hurts because the MRI will not show it. This is a big problem because the annular tears that cause pain look just like the ones that don’t and as I said, most don’t hurt.

More confusion arises because the MRI doesn’t reveal all annular tears. The MRI can be read as normal and yet an annular tear can be present. This can be a huge problem for the patient seeing a doctor who is content to rely exclusively on the MRI for a diagnosis. Since annular tears aren’t always seen on the MRI, it is often assumed that the person is imagining or exaggerating their low back pain.

In my experience, this is the most frustrated patient I see in the office.

Let’s Profile The Annular Tear Patient.

You are most likely between age 20-60 and can be male or female. The most common complaint is Low Back Pain. Low back pain can be aggravated by sitting, but there can be buttock or leg pain too. You may have had a back injury of some sort.

Common examples are doing a deadlifts in the gym or being in a motor vehicle accident, but it could be anything. The pain has gone on for many years. It’s usually deep and aching, and intermittent. It can just come and go without warning. It is often described as “my back just goes out for no particular reason.” When your back goes out, it can be very disabling and require days of bed rest, then there can be long periods of no back pain. This story in conjunction with the minimal or small changes seen on the MRI seems to confuse everyone, but the pain and suffering continues.

The history is very important and after hearing the same story so many times, I can often make the diagnosis over the phone.

Here are the 7 most typical complaints for someone with a toxic annular tear.

- “The pain is usually worse when I sit and gets worse with exercise (including PT) and stretching.”(Chiropractic adjustments can help for a short time, but the pain usually returns. Decompression devices don’t help too much either).

- “My back just goes out, but it can be fine for months and then it will go out, for no reason. When it goes out, I’m really disabled for a few days or a couple of weeks. I’ve had this problem for years.”

- “Driving the car for any length of time is unbearable because of the pain.”

- “I’ve seen several doctors and they all say that my MRI looks normal. They tell me to just live with it or do more therapy.”

- “I have groin or testicular pain, but my doctor tells me that my hips are normal.”

- “Pain pills might take the edge off, but don’t really do much to help with the pain.”

- “I have intermittent pain, numbness, or burning in one or both of my legs, buttocks or feet, but I don’t have a herniated disc.”

These are common repetitive complaints of someone with an annular tear and if you see enough doctors, they will begin to question your sanity.

I want you to listen to Darin, he gives the classical history for an annular tear. He lives in a major metropolitan area and saw 16 medical professionals over a 2-3 year period of time, 12 of which were MDs. Nobody knew the cause of his back pain.

Listen to Darin’s Story

Darin's story is classic. You can hear his frustration mounting as he tries to get someone to explain why his back is hurting so much. This is a patient with a long history of very disabling complaints.

We would expect to see something significant on the MRI scan to account for his symptoms, but nobody does. Given the length of time you have had your symptoms, it’s strange that nobody seems to suggest a different way to investigate and diagnose your problem.

What’s going on here?

Let's talk about how to diagnose a painful toxic annular tear in part 2.

Part 2 - What is The Best Way to Diagnose an Annular Tear?

This is part two of Toxic Annular Tears of the Lumbar Spine, The Best Way to Diagnose an Annular Tear.

In part one, we saw the frustration of struggling with chronic low back pain without getting a diagnosis. One of the most common things I hear in the office is “Nobody can tell me why my back hurts when I’m sitting,” or “why does my back to go out all the time.”

These are common complaints from people who have struggled for years with low back pain. These people have usually seen several specialists and had at least one MRI.

The MRI Doesn’t Show Much

Unfortunately, the MRI often shows “minimal changes” like a bulge or mild degenerative changes, sometimes it’s read as “normal”. The doctor looking at the MRI films often tells you that your complaints and pain seem out of proportion to the MRI findings. You might even start to question yourself and you will likely seek a 2nd opinion. The second opinion will likely reflect the same sentiments as the first examiner. If you have groin pain or genital pain or numbness in addition to the back pain, things can seem even more confusing.

What’s the problem here?

The problem is that you don’t have a diagnosis yet. The MRI is not the gold standard for diagnosing an annular tear.

What is the best way to diagnose an annular tear?

Before we answer that question, it’s important to remember two very important facts.

The first fact is that there is no single or perfect imaging study. They all look at the body from a different perspective.

For example, an MRI is excellent at showing soft tissues and water content, whereas an x-ray or CT scan can see bone and contrast better.

The second fact is that imagining studies can only image or show pictures, they cannot tell if something is causing pain. This is very important because there are occasions where the MRI will show an annular tear or fissure, but it is not the cause of the back pain. In other words, the finding of an annular tear does not correlate very well with the pain.

What does the MRI show?

There are three things often seen on the MRI used to evaluate back pain.

- A black disc - is defined by Spine-Health to describe a dehydrated and totally degenerated spinal disc. It derives its name from the way it is seen on an MRI scan as black in color.

- A high intensity zone (HIZ) This is a bright spot Which may represent edema (water signal) at the end of an annular fissure or tear.

- A disc bulge A disc bulge is defined as extending 3mm or less beyond the vertebrae. If there is anything less impressive or more common than a disc bulge on an MRI scan, I’d like to know what it is. Disc bulges are very common in people over the age of 50.

These three findings that may not be considered normal on an MRI, but they are commonly seen and don’t correlate well with back pain.

As a matter of fact, some large studies ONLY associate disc degeneration and disc bulges with pain, not a high intensity zone (HIZ) or annular fissure! HIZ’s and annular fissures are commonly found in completely asymptomatic people.

Unfortunately, the MRI is where the investigation usually stops, even when the pain persists.

So what is the best way to diagnose an annular tear?

The answer is a CT discogram. This is the best way to diagnose and document an annular tear and should be considered as the gold standard.

The discogram is an invasive procedure where a small needle is placed in the disc using fluoroscopy to guide the needle placement. The purpose of the needle is to inject the dye or contrast.

If the discogram is performed under mild conscious sedation, it can be provocative. Provocative means that the pressure created when injecting the dye into the disc, might mimic the old back pain. If the patient describes the pain as similar or the same as the disabling back pain, it is considered “concordant”. The idea of concordance is not perfect but if positive, it lends more weight to the discovery of the diagnosis of the painful disc.

This is not a perfect test, but it can be very convincing when someone says, “yes, that’s my back pain” when injecting the dye. The correlation gets stronger if the dye leaks out of the disc (annular tear) on the x-ray taken at the time as the discogram.

How do you know what part of the disc is leaking?

The fact is that you cannot tell right from left on an x-ray taken in surgery when doing the discogram. Sometimes there isn’t enough dye leaking to see it clearly on an x-ray.

How can we get a clearer picture?

The CT is the best way to see where the dye is. Follow the discogram with a CT scan. The discogram puts the dye in the disc, then the patient is taken to a CT scanner within an hour or so after the discogram. The spine is scanned to look at the discs and to determine whether the dye is properly contained or whether it is leaking out, through an annular tear. The annular tear can occur on the right, left, center or all the above. It is helpful to see if the location of the tear correlates to the side of the back pain.

We now have a diagnosis, which is the most important thing to guide treatment. Without a diagnosis, you are just flying in the clouds.

Next is part 3, What an Annular Tear is and Why do They Hurt?

When you understand this, the treatment options will make a lot more sense.

Part 3 - What is an Annular Tear and Why Do They Hurt?

In part one, we saw and heard the frustration of struggling with chronic low back pain without getting a diagnosis.

In part two, we talked about why the CT discogram is the gold standard to diagnose an annular tear.

In this part, we will examine what an annular tear is and look at some of the reasons they just keep hurting.

What is an Annular Tear?

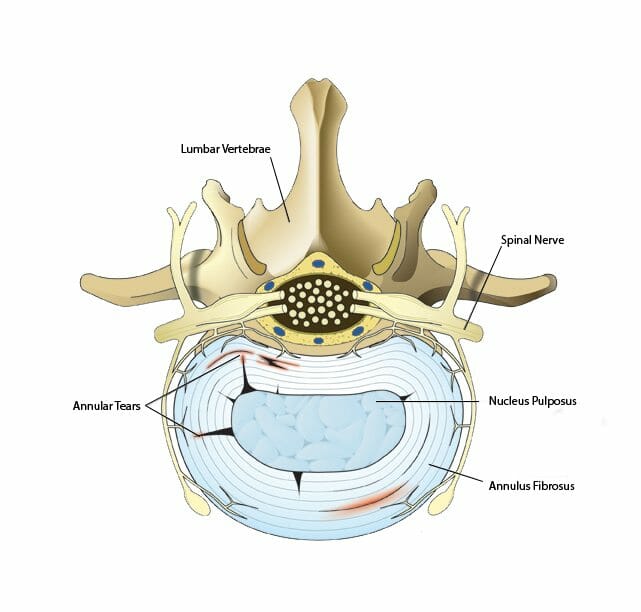

Your Spinal column has 33 vertebrae and the top three-quarters of which are separated by discs. These discs, 23 in all, serve to cushion and protect the vertebrae; they absorb shock and help to keep weight in the back evenly distributed. The inside of the disc, the nucleus, is made of a soft, gelatinous fluid, and the outer half is made of tough connective fibers called the annulus fibrosus.

As we get older, the vertebral discs can start to exhibit wear and cause some health problems. A common problem is a tear in the annulus fibrosus, or annular fibers commonly referred to as an annular tear.

Annular tears usually occur in the lumbar spine or the lower back. In most cases, the tears happen not from the outside in, but from the inside out; they start in the nucleus.

When annular tears are minor or just in the beginning stages, they may not cause any discomfort. However, if the tear gets progressively worse, the gel-like fluid in the disc can start to leak out. This may not seem like it can do a lot of damage, but when the fluid hits the spinal nerves, it can cause a lot of pain.

What are the 3 main factors that cause pain?

As mentioned above, a leading cause of annular tears is simply getting older. Vertebral discs lose their durability with age, and the weakened annular fibers can start to tear. Excess body weight can also lead to annular tears, as it can be extremely taxing on the vertebrae and discs. Twisting motions can also put small tears in the annulus fibrosus, especially if they’re coupled with lifting a lot of weight or moving too suddenly. Similarly, individuals who have been in car accidents may also suffer from annular tears.

There are three main factors that contribute to annular tear pain:

- Mechanical

- Chemical

- Immunogenic

If this sounds complicated, it is. One thing I have learned over the years is that if there is a common problem that affects a lot of people and it doesn’t get solved after a while, then it’s a complicated issue. Let’s see how much of this problem we can unravel.

Mechanical issues

Mechanical issues are the easiest to understand. The thick annulus is what wraps itself around the softer center of the disc, or nucleus, to keep it in place. The annulus is constructed like a radial tire with fibers running in multiple directions for strength and the ability to resist torsional and compressive forces of motion. This makes the annulus a complex structure that is moving continuously and subject to constant wear and tear, even while laying down.

This means that tears are complex and can go in many different directions. Tears can originate in almost any location. The complex structure and continuous motion of the annulus only sets the stage for mechanical issues. We must consider the environment that the annulus exists in.

The environment of the annulus is suboptimal, given all that it is required to do. First, the blood supply is not great. The more active a structure is, the more blood it needs. Given its requirements, the disc does not really have much of a blood supply, neither to the nucleus or the annulus.

The blood delivers oxygen and nutrients and then removes metabolic waste products. The blood vessels supply circulation to the annulus only; there is no real circulation to the nucleus itself. It follows that if the blood supply and oxygen tension are marginal, then the healing of the annulus is going to be slow too. If metabolic waste products build up too quickly, then an acidic environment slows healing down even more. On top of this, the spine moves continuously; it moves even when we think we are at rest.

There are substantial forces of compression and torsion, or twisting, that the annulus is continuously subjected to these stresses and strains, no matter what position we are in. In short, there is no down time or rest for the annulus.

The most obvious example of an annular tear is a herniated disc. The annulus must tear in order to get a disc herniation. The tear provides the pathway for the fragment of nucleus to herniate out from the center of the disc.

People don’t usually talk about a herniated disc and annular tear in the same sentence, but the fact is that you must have an annular tear to have a disc herniation. This fact will also explain another phenomenon – having a disc herniation on one side of the body and feeling pain on the opposite leg. (We’ll talk about this later)

But what if the nuclear fragment doesn’t herniate all the way out?

What if the fragment doesn’t herniate out far enough to cause leg pain, but instead gets stuck in the annular tear?

If the fragment is interposed between the edges of normal annulus tissue, then the annulus is not going to be able to heal in the long or the short term. The edges of the torn annulus can’t heal because the disc fragment is in the way and the annular edges can’t touch. This is where the blood supply issue becomes important. There may not be enough blood passing through the area to resorb the fragment, it just stays there.

Consider this, if a disc fragment moves in and out of the annular tear then this can explain the feeling of “my back going out.” When your back goes out, the fragment is in the wrong position in the annular tear and really hurts. If the fragment is in good position then the pain goes away.

Chemical Causes Of Back Pain

The next two causes of pain are chemical and immunogenic. Although they are different in how they occur, the final pathway to pain is the same – Inflammation! The pain that you feel in your back is a result of inflammation.

In the case of an annular tear, there are often fragments of nucleus that have broken off and have nowhere to go. They are just stuck inside the disc as they start to break down. The chemical byproducts of disc fragment breakdown turn out to be very inflammatory and act as a painful stimulus to any tissue they come in contact with.

Examples of the inflammatory chemicals detected are interleukins, TNF alpha, and cytokines released from blood cells (macrophages) that help with the cleanup of injured tissues (torn annulus and ruptured disc fragments). As long as the fragments are present, the inflammatory chemicals will continue to be produced and back pain will continue.

The leakage of these inflammatory chemicals completely through a tear in the annulus will result in stimulation of the nerves that pass over the back of the discs, like the nerves of the cauda equina, that goes to your buttocks, legs and feet. The nerves stimulated by the chemicals can cause a variety of sensations from numbness, pain, burning and cold. Your complaints can confuse the clinician looking at you because you have extremity pain, but no disc herniation.

This explains how are you get extremity symptoms without a herniation? The annular tear is providing a pathway for inflammatory chemicals to be in contact with your nerves passing over the annular tear.

Can your immune system reject part of your disc?

The answer to this question is yes.

Apparently, not all disc material is “immunologically privileged”. The immunogenic cause of pain centers around the fact that disc tissue can trigger an immunogenic (inflammatory) response. This occurs when the normal blood supply responsible for healing comes in contact with the disc fragment and “rejects” it.

At this point, the white cells respond with a “rejection response” and the chemicals released sensitize the surrounding nerve and vascular tissues that are trying to heal the tear. The immune response sensitizes and inflames small nerves inside the disc which is interpreted as back pain.

The 3 Possible Reasons of Why Annular Tears Can Hurt You.

- Mechanical – Disc fragments can be interposed in the annular tear, which prevents normal healing of the annulus.

- Inflammation – Disc fragments that are breaking down inside of the disc can release inflammatory chemicals like cytokines and TNA alpha. These inflammatory chemicals can sensitize nerves in the annulus or leak out of the disc and sensitize the nerves going to the buttock, legs and feet.

Immunogenic – The chemicals released during an immune response to disc fragments that are not “privileged”. The chemicals can sensitize the small sensory nerves that accompany the vascular (blood vessel) ingrowth sent to repair the annular tear. The sensitized sensory nerves can cause pain.

Part 4 - Confusing Pain Patterns

Confusing pain patterns or why doctors think you are crazy

Call the annular tear the chameleon of back pain if you like. It is confusing because it has so many presentations, in different locations and with different sensations. It is difficult and sometimes embarrassing to describe. What’s worse is the fact that there is often very little seen on the MRI to account for your complaints.

“I’ve seen several doctors and nobody has an answer.”

People with symptomatic annular tears are often mystified because they have no idea about what’s bothering them (and they don’t usually get much more insight from the medical community). Since the pain can be disabling, you expect to visit a doctor and have a diagnosis and a plan of action, but things rarely work out this way.

As you describe your symptoms, which can be quite variable, there is not much seen on the MRI to account for the pain. Buttock, thigh, leg, and foot pain are common places to feel pain. But what about the pain or burning felt in the groin, or genital area?

It’s not unusual for patients with an annular tear to have seen a general surgeon to rule out an inguinal hernia or a hip specialist to see if there is a problem with the hip joints.

Since the doctor you initially visited for your back pain didn’t give you any answers, you might see another specialist or so. I saw a very frustrated patient that saw 12 specialists that gave him no answers, I was 13th specialist and the CT discogram showed the problem.

I don’t know why the pain is felt in the groin or genitals. Perhaps it is a pain that is referred from the sensitive annulus or perhaps it’s the sacral nerves of the cauda equina that are being stimulated as they pass over the leaking annular tear. Sensations of pain, numbness and cold water are all mentioned.

Your doctor says “the other leg is the one that’s supposed to hurt.”

You take your MRI to the specialist to help evaluate your leg (sciatica) and back pain. The report and the films confuse everyone. Was there a problem with the labeling of right and left on the MRI? Why does the report and MRI show a disc herniation on one side, but you hurt on the side opposite of the herniation?

This does seem confusing at first, but remember that I said that annular tears must be present with any disc herniation. What’s to say that there is not more than one annular tear? Perhaps there is one created be the disc herniation and another one not seen on the MRI, but located on the opposite side of the herniation. The tear on the opposite side is leaking on the leg nerve passing over the tear.

The Recommended Treatments Cause More Pain

The most common treatment the medical professional recommends is PT or physical therapy. Most patients that have an annular tear will complain that PT makes them worse.

Chiropractic adjustments don’t last long and dynamic traction doesn’t seem to work very well either. Even vigorous stretching can cause a flare of the pain.

What is the worst position?

If I had to select one position as the most painful, it would be sitting, especially when driving

“My back just goes out.”

This has to be one of the hallmark complaints. The pain will be fine for weeks or months and then just “goes out”. When it “goes out”, it can be out for several days and requires limited activity or bed rest to “go back in”. An annular tear is really a chronic condition and in many cases, they just don’t go away because the fragment doesn’t go away.

I have thought about this complaint many times and I attribute it to a fragment that moves in and out of the “correct” position. Comfort depends on the fragment position being in the right or wrong place. It can be continuously painful if the fragment stays in the wrong place.

The verbal descriptions above are very common when someone has an annular tear. One can almost make the diagnosis of an annular tear just by listening to the history. The next step, of course, is to confirm the diagnosis with a CT discogram.

Part 5 - Treatment Options For Annular Tears

Welcome back to Toxic Annular Tears of the Lumbar Spine. Finally, we get to part five, treatment options for annular tears.

Throughout this presentation, I’ve tried to emphasize making an accurate diagnosis of your back pain. An accurate diagnosis is the most important thing to understand in any disease process to pick the best treatment. This is especially true when performing endoscopic spinal surgery, where the approach is so small, the diagnosis must be spot on.

Endoscopic spine surgery requires a good understanding of which pain generator is causing the pain in order to select the best approach. When dealing with back pain, there is a big difference when treating an annular tear versus facet syndrome. There is no such thing as “exploratory” Endoscopic spine surgery; you must have a plan of what to do.

I’m not sure that making the exact diagnosis is nearly so important before performing a fusion, since the goal of a fusion is to immobilize a segment of the spine and if one guesses the correct level, that’s all that needs to be done.

In part three of this series, we showed three possible reasons that Annular tears might hurt.

- Mechanical – Interposed tissue prevents healing.

- Inflammatory – chemical cytokines released from dead tissues.

- Immunogenic – Neo-vascular sensitivity.

These potential sources of pain might occur alone or in combination and I’m not sure how to distinguish them beforehand, so we must assume all the possibilities are present.

I have outlined the possible reasons that annular tears hurt, so now we can look at the treatment options and why they may or may not work.

Now, because the annulus fibrosus has such a limited blood supply (a necessary component for the body to repair itself), annular tears can take quite a long time to heal on its own — 18 months to two years.

The majority of doctors will start with a conservative approach to treatment, prescribing anti-inflammatory medication to relieve the pressure and possibly steroid injections to alleviate the pain. Regular chiropractic treatments, spinal traction therapy, and physical therapy can also bring relief to individuals suffering from annular tears.

If these conservative treatments are not effective, then surgical treatment may be necessary. Annular tears can be sealed off with a laser procedure to prevent any further injury. Or, a minimally invasive procedure called an endoscopic discectomy can be effective if there is a painful loose disc fragment in an annular tear. In more severe cases, disc replacement or spinal fusion surgery can replace a damaged disc.

There are also some highly advanced treatment options that are in development. For example, using a patient’s stem cells to regenerate their annular fibers. However, these treatments are only used on a case by case basis.

If you are experiencing back pain that isn’t getting better with rest and a decrease in activity, then you’ll want to see your doctor. Severe annular tears, when left untreated, can lead to more painful conditions, such as a herniated disc. A good treatment plan can relieve your discomfort, return you to your preferred level of activity, and keep your back healthy and pain-free.

Various Treatment Options For Annular Tears

- Tincture of time

- Thermal ablation (IDET)

- Disc injection (Biologics)

- Endoscopic cleanup with thermal ablation

- Disc replacement or fusion

An annular tear is a problem of the disc that includes both nucleus and annulus. It’s important to consider treatment options in terms of safety, risk, and effectiveness. In terms of risks, it is lowest when doing nothing but letting time pass and the most when considering a fusion or disc replacement. On the other hand, if you do nothing, it may be very safe but not very effective.

What about Tincture of Time?

If you look at the literature, it recommends that you wait for 12-18 months of conservative therapy before considering anything else. There is no particular regimen of therapy that seems uniformly successful so people will often try a few things like physical therapy, chiropractic, or spinal decompression. There is usually little lasting relief from these regimens and one common complaint I hear is that physical therapy actually makes things worse.

The recommendation to wait 12-18 months will lot will depend on how well you can tolerate your back pain in the course of your life and daily activities. The natural history of back pain “coming and going” is likely the history of an annular tear. Since the pain waxes and wanes, you hope that one time it will just go away and stay away, but it rarely just goes away. You can spend a lot of time going from doctor to doctor trying to figure out what the problem is, often without much luck.

I don’t like chronic pain, it just gets harder and harder to get rid of. I also don’t like to see back pain go on for months and months without making a diagnosis. Chronic pain can change posture and can create other problems. Other problems or side effects may result from any medications or narcotics being used to treat the pain. If the back pain goes beyond 3-6 months, a diagnosis needs to be made, so treatment options can be discussed.

The initial “MD approach” to back pain is often to prescribe pills (narcotics, muscle relaxants, or anti-inflammatories) and physical therapy); this is probably reasonable since most back pain will resolve by itself in 4-8 weeks, but if things aren’t getting better in 6-8 weeks, then one should start seeking a diagnosis.

The chiropractic or spinal decompression approach is a more natural approach that does not use drugs, but the idea is the same if you are not getting better. Don’t just keep doing things that don’t make you better, work on getting a diagnosis if your back pain persists in spite of conservative therapy.

Thermal ablation

IDET Intradiscal electrothermal therapy (thermal ablation) is mentioned for historical completeness. A heating probe was inserted into the disc with fluoroscopic guidance and then heated up. It was originally used to treat some very specific disc herniations.

Although appealing in concept, it did not give results better than a placebo for the treatment of low back pain. IDET tried to use heat to alter disc sensitivity and chemistry. In this type of procedure there is no direct visualization, and there was no way to see or remove disc fragments that could get stuck in an annular tear. IDET is not done these days.

What about Disc injections (Biologics)?

In terms of risk, safety, and benefit, the first thing people might think about is an injection inside of the disc to alter the chemical environment or sensitivity. Let’s look to see what’s been done in this area.

Chymopapain is a proteolytic enzyme derived from papaya fruit, which was injected into the disc in order to dissolve it. Many years ago I worked in an office that had one of the first FDA approvals for the use of it to treat disc herniations. It was a successful treatment of disc herniations that caused radicular or leg pain, but was not very effective to relieve axial back pain according to my senior partner at that time. It’s hard to know why it didn’t work better.

Prolotherapy injections were described in the 1950’s as a way to treat the painful joints. Derby and Eek published a paper in 2004 about injecting a prolotherapy solution into painful discs. The prolotherapy solution consisted of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate combined with hypertonic dextrose and dimethylsulfoxide. The injections resulted in significant relief of pain in about 65% of the people injected.

I treated many people with a variation of this injection in the mid 2000’s and the results were very similar to those published in the study. These results are quite good considering the low risk, low cost and safety of the injections. The injections alter the chemical environment inside of the disc. The injection reduces inflammation and sensitivity inside the disc. The exact mechanism of action was not described. One reason it may not work better, is that there is no mechanical debridement or removal of the degenerated disc fragments.

Biologics are on everyone’s mind. The prolotherapy injection mentioned above is an attempt to alter the environment of the inside of a disc to promote healing, but new cells are not being created. I believe that some type of disc restorative solution (a biologic) is not that far off from being created, but we are not there yet. Such a regenerative solution will stimulate new cell growth in a relatively hostile environment. This will be a fascinating endeavor that will use some combination of stem or progenitor cells, perhaps in combination with some growth factors.

Transforaminal Endoscopic Cleanup with Thermal Ablation

This approach makes sense because it addresses the three main causes of pain from the annular tear:

- Mechanical

- Chemical

- Neo-Vascular Sensitivity

This procedure is performed with a 7mm endoscope that enters the disc through an atraumatic transforaminal approach. The tip of the scope contains a camera, light source, irrigation port, and working channel that instruments can be passed through. This scope is very similar to a knee arthroscopy that revolutionized the surgical treatment of the knee.

The disc is stained at the beginning of the surgery. Methylene blue stains tissue is not viable (loose fragments are not viable).

The scope has 4 parts to the tip:

- Light source

- Camera

- Irrigation port (constant water flow)

- Working channel through the center of the scope to pass instruments through.

The mechanical issue of an annular tear is loose disc fragments. Disc fragments can be visualized and be washed or pulled out. The annular tears and fissures can be probed to be sure there are no more fragments interposed in the tears.

Chemical sensitivity is addressed by constant irrigation that will wash out small debris as well as inflammatory chemicals inside of the disc. Perhaps the normal chemistry of the disc can be re-established with the washout that occurs while removing the fragments.

Small sensitive sensory nerves grow with the small blood vessels that try to heal the annular tear. If the nerves are sensitized as a result of the immune response, pain can occur. A thermal ablation probe (passed through the working channel) can destroy inflamed nerves and blood vessels on contact. Direct vision is used to guide the heating probe to the areas of inflammation.

I like the endoscopic transforaminal “washout” because it addresses all three causes of annular tear pain with minimal risk. Dr. Tony Yeung published a abstract on this technique and reported satisfactory results in 73.5% of patients in his study. Results were excellent in 15%, good in 28.3%, fair in 30.1% and poor in 26.5% of the patients. I have used this treatment for many years and have very similar results. These results seem very reasonable when you consider the alternatives.

Fusions and Disc Replacements

Fusions and disc replacements are the extreme end of the treatment spectrum for painful annular tears. Although better accepted and more thoroughly studied, the fusion technique has a 65-80% satisfaction rate, so if you are not satisfied with your result, there is not much you will be able to do to change it (it’s irreversible). The risks and potential for serious complications are greater after a spinal fusion. There are short term and long term (adjacent disc disease) complications and the recovery is 3-9 months.

In many ways, it’s hard to know why a fusion is not more successful since the entire disc is removed. Your options are very limited after an unsuccessful fusion.

There are a lot of options when you deal with a painful toxic annular tear. Unfortunately none are definitive, but there is a gradation or progression of treatment from lower to higher risk. As I said in the beginning, the most important thing to get the ball rolling is to make a good diagnosis and then look at your options moving forward.